More than half a century after it was designed, Allan Fleming’s CN monogram still looks like it could’ve been created today. Designers around the world often choose it amongst their favourite marks. Here are the lesser known logos that preceded it.

Much of the following information is courtesy of CN.

1852: Grand Trunk Railway

CN’s logo dates back to the birth of Canada’s first major railroad, the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR), a line that eventually joined others to form CN.

Built originally to link Montreal and Toronto in the 1850s, GTR saw its future as an international railroad serving markets on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border — a feat that it accomplished within a decade.

Grand Trunk Railway map, via Victorian Wars Forum

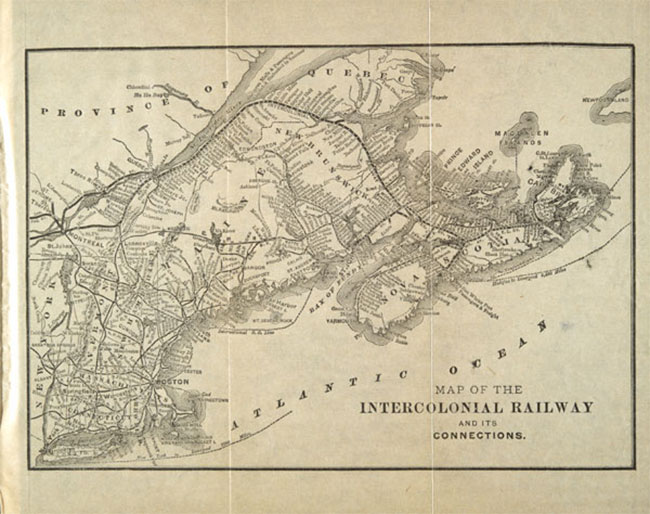

1883: Intercolonial Railway

Built during the 1870s, the Intercolonial Railway (ICR) was another railroad that eventually joined others as part of CN. It linked Nova Scotia and New Brunswick with Quebec.

Its logo proudly dubbed the line the “People’s Railway” and adopted the moose as its trademark due to its superiority in the animal kingdom and, in turn, its ability to hold its own against all rivals in its domain.

Intercolonial Railway map, via Library and Archives Canada

1896: Grand Trunk Railway System

Under new general manager Charles Melville Hays (a victim of the Titanic), the Grand Trunk Railway adopted a more aggressive management style — and a new logo to express the change.

Hays set about modernising and expanding the British-owned railroad, renaming it “Grand Trunk Railway System” to reflect its far-flung interests.

A version of the logo was the so-called “tilted wafer” — the company name on a square tilted nine degrees downward to the left, presumably an eye-catching device to convey motion. However, the logo’s simple lines didn’t please everyone. One observer thought it was “the most prosaic” of the major Canadian railroad logos.

Grand Trunk Railway System timetables 1898, via railroads.uni.edu

1899: Canadian Northern Railway

The Canadian Northern Railway resulted from the ambitions of two energetic, small-town-Ontario rail promoters, William Mackenzie and Donald Mann.

After acquiring a couple of small Manitoba lines in the mid-1890s, Mackenzie and Mann incorporated the Canadian Northern in 1899 and began expanding rapidly both east and west.

Canadian Northern reduced rates 1904, via Library and Archives Canada

By October 1918, Canadian Northern had fallen victim to its own ambitions and economic forces beyond its control. Beset by declining revenue, rising costs, and lack of capital during World War I, it teetered for a time on the brink of bankruptcy. The railway was taken over by the Canadian Government in August 1917 — only to become one of CN’s constituent lines in 1919.

The logo of Canadian Northern Railway would serve as a prototype for CN’s logo during the first few years of its existence. Essentially, CN took the easy way out and simply replaced the “Northern” in the Canadian Northern logo with the word “National.”

1905: Grand Trunk Pacific

At the turn of the century, Canada was riding high on an economic boom. Confined to eastern Canada, the Grand Trunk Railway under expansion-minded Charles Hays felt boxed in and longed for a piece of the action.

Meanwhile, the Government was convinced that Canada needed and could easily support at least one more transcontinental rail line. A second coast-to-coast railroad would also break Canadian Pacific’s monopoly in the west.

So Grand Trunk and the Government got together to construct a third east-west line. GTR incorporated a subsidiary, the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTP), in 1903, which would run between Winnipeg and Prince Rupert. The Government, meanwhile, would build the eastern portion, known as the National Transcontinental Railway (NTR), from Winnipeg to Moncton.

Grand Trunk Pacific’s logo was derived from its parent’s logo, featuring the “tilted wafer.” It bore the words “The Only All-Canadian Transcontinental Route” — perhaps an act of one-upmanship over rival Canadian Pacific, which reached its eastern terminus via the state of Maine.

Grand Trunk Pacific farmland ad 1913, via Ben Bradley

A similar tilted wafer with the slogan “The Transcontinental Line” was also used to identify the GTP/NTR system. But like Canadian Northern, GTP came to grief during the economic turmoil of World War I. The Canadian Government nationalised the property in 1919.

1915: Canadian Government Railways

The term Canadian Government Railways (CGR) was a catch-all phrase used to describe a group of railroads owned by the government of Canada in the early part of the 20th century.

Each of the railroads making up CGR was managed independently. In 1915 the group included:

- The Intercolonial Railway (Government-owned since its inception in 1867)

- The National Transcontinental Railway (also Government-owned from its start in the early 1900s)

- The Prince Edward Island Railway (taken over soon after Prince Edward Island joined Confederation in 1873)

- The yet-to-be-completed Hudson Bay Railway (a Government-propelled project all along)

- To these ranks the Canadian Northern Railway was added in September 1917, shortly after a Government takeover

Canadian Government Railways had a simple logo, but apart from that unifying device, the line had a shadowy existence with very little real substance or organisation.

1919: Canadian National Railways

The name “Canadian National Railways” first appeared officially on December 20, 1918, when the Government authorised that term as a descriptive name for the various properties that made up Canadian Government Railways — principally, Canadian Northern, National Transcontinental and Intercolonial.

Six months later, on June 6, 1919, Parliament passed legislation to incorporate the Canadian National Railway Company Limited — and CN was born. The following year, the Grand Trunk Pacific was added to the line-up, giving the new railroad two transcontinental networks.

With so many component parts, each with its own strong identity, CN struggled to craft a single, recognisable face to show the world. During the first few years, it took the easy way out and used two different logos, each one mimicking the trademark of a predecessor railroad. Equipment and sign painters simply replaced the “Northern” in the Canadian Northern logo and the “Government” in the Canadian Government Railways logo with the word “National.” A practical and economical solution, perhaps, but it did little to foster a clear conception of the new railroad in the public’s mind.

The two logos CN used during this period were usually printed in black or white according to the desired contrast with the background.

1923: Canadian National Railways

The finishing touch to the creation of Canadian National Railways came early in 1923 when the Grand Trunk Railway joined the system after a Government takeover some three years earlier. That event quickly led to a unified corporate image for the new railroad, one it would display with few major alterations for 38 years.

CN abandoned the stop-gap solutions of its first few years and introduced a single design to represent the entire company. But like the two earlier versions, the new logo reflected CN’s parentage — this time, the Grand Trunk and its familiar “tilted wafer.”

At first, CN used a square-shaped wafer, just as GTR did. Then, in 1927, the square became a rectangle, presumably to accommodate longer yet fewer words.

The red used in the logo was CN No. 10, which is close to Pantone 200c. The lettering was gold on equipment, for which there is no good Pantone equivalent. In print, however, the yellow employed to represent gold was close to Pantone 115c.

1943: Canadian National Railways

During much of the first decade, President Sir Henry Thornton had led the company with great panache, expanding into fields as diverse as radio broadcasting, resort hotels and ocean liners. Then came the Crash of 1929. While business plummeted and hostile politicians clamoured for an end to the publicly owned system and its “extravagance,” CN stumbled through much of the Dirty Thirties.

But when World War II broke out in 1939, CN seized the opportunity to demonstrate its value to the nation. It performed prodigiously in the war effort, turning handsome profits as well.

The first significant change to CN’s logo came in 1943, 20 years after it had been adopted. In a sense, the modified logo symbolised the railroad truly coming into its own and hitting stride after two decades of struggling to define its role.

Buoyed by patriotism and a new sense of mission, CN superimposed the tilted wafer on a maple leaf, creating a new logo with built-in flexibility. First applied to a new batch of boxcars in 1943, the logo featured “CNR” above the wafer, while the slogan “Serves All Canada” replaced “Canadian National” on the wafer.

Variations on the theme would appear in later years — different colour schemes and alternate slogans, such as “Canada’s Largest Railway.” CN continued to use an unadorned wafer for some applications, but for the most part, the instantly recognisable maple leaf and the nearly ubiquitous slogan “Serves All Canada” became synonymous with Canadian National.

CNR emblem, via Gary DB

The maple leaf was Green No. 12, for which Pantone 363c is a good match. The rest of the logo usually appeared in white against whatever the background colour was: brown on boxcars (Pantone 174c) or orange on cabooses (Pantone 166c).

1954: Canadian National Railways

Emerging exhausted from the extreme demands of World War II, CN badly needed modernising and energising if it was to hold its own against growing car and truck competition. Donald Gordon, who became President in 1950, was just the man for the job.

Gordon transformed the railroad from the ground up, replacing steam with diesel power, introducing computer technology, restoring the worn-out freight car fleet, and recruiting and training a highly skilled management team.

CN was changing rapidly — but the changes were happening largely beneath the surface, virtually invisible to the public eye. Yet CN initiated just one relatively minor modification to its corporate symbol during the 1950s, barely reflecting the immense progress underway.

In 1954, to mark the arrival of new passenger cars equipped with unprecedented amenities, CN eliminated the wafer’s tilt and redrew it as a straight square on the maple leaf. As changes go, it was hardly dramatic — but it did have the virtue of being easier to apply to CN’s mammoth locomotives and railcars.

Canadian National Railways locomotive, via Mike Robbins

The maple leaf was CN Red No. 10 (Pantone 200c), the wafer was black, and the lettering simulated gold (Pantone 115c).

1960: CN

The story begins in 1959 when a revitalised and confident CN surveyed Canadians’ attitudes to see how it measured up in the public mind. The findings came as a great shock: when people thought of CN, they pictured an “old-fashioned,” “backward” organisation, hostile to innovation — the very opposite of what the company was trying to achieve.

Dick Wright, head of public relations at the time, firmly believed that “seeing is believing.” If CN had a fresh new trademark, he reasoned, people would be more likely to think of it as the customer-friendly, technologically advanced railroad it was rapidly becoming. Wright commissioned New York designer James Valkus to study the problem. Valkus became convinced that what CN needed was not just a new trademark but a complete overhaul of its visual image — from locomotive paint schemes and building exteriors right down to the sugar packets used on passenger trains.

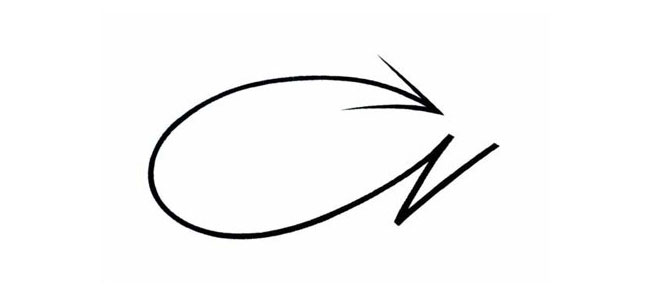

A new logo would be the heart of the redesign program. It had to be perfect from both an aesthetic and a practical point of view. It had to communicate the essence of the new CN: powerful, progressive, dynamic. Valkus assigned the challenge to Allan Fleming a young and highly regarded Canadian graphic designer. After experimenting with countless possibilities, Fleming hit on a particularly inspired design while sitting on a New York-bound airplane. He quickly sketched the idea on a cocktail napkin — and CN’s logo was conceived.

CN logo sketches via designKULTUR

Handwritten note from James Valkus

It was a dramatic contrast to the existing image. Out went the maple leaf, out went the time-worn wafer. Indeed, out went the “CNR.” Fleming had come up with a way of combining the “C” and the “N” in a harmonious, evocative manner. Abolishing the “R” made the logo bilingual (“Canadien national” as well as “Canadian National”). Without the “R” for “Railways”, the logo could be used as a unifying mark that would also serve the many non-rail businesses CN ran at the time — hotels, telecommunications and ferry services, to name a few.

Fleming avoided literal symbols — no animals or vegetables allowed — because they tend to show their age very quickly. As Fleming put it: “A literal drawing in 1944 of an object — even a plant leaf — looks in 1954 as if it was drawn in 1944. After five, 10 or 15 years, that symbol would have to be revised. In fact, CN itself has had that history up to now — of constantly revising its trademark bit by bit — and every time it has been revised the one before it is out of date, and it costs a lot of money and a lot of hard work to keep ahead of the game.”

Photo via everkamp

While conceptualising the future, Fleming drew on the past for the kind of image that would convey timelessness. Studying the Christian cross and the Egyptian symbol for life, he borrowed the idea of using a line of single thickness. “The single thickness stroke is what makes the symbol live,” Fleming later said. “Anything else would lack the immediacy and vigor.”

Allan Robb Fleming, via

The continuous flowing line symbolised “the movement of people, materials, and messages from one point to another,” Fleming said. As the eye moves from “C” to “N,” the image suggests fluidity and motion. “It’s a route line that incidentally spells CN,” Fleming explained.

Photo by Tim Stevens

More about Fleming’s mark in the CN visual identity guidelines (PDF).

This post in its entirety was reproduced from http://www.logodesignlove.com

0 Comments